During the climate summit, everyone saw the water melting. Only a few understood what it really meant.

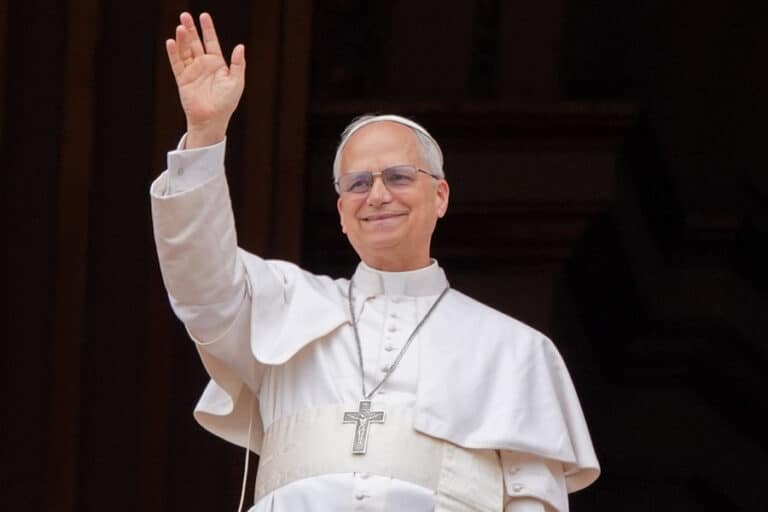

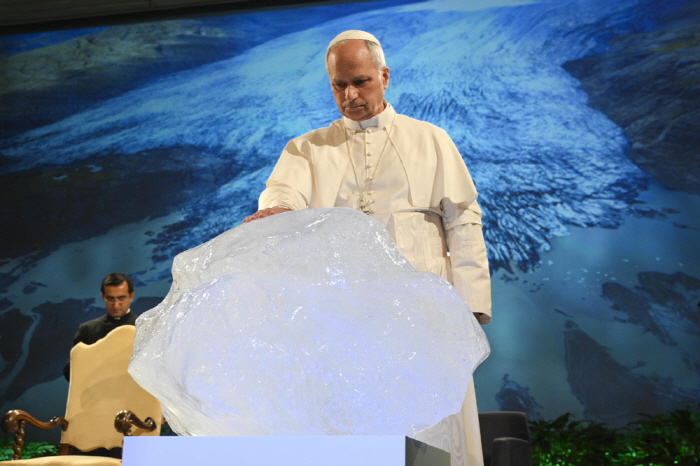

When Pope Leo XIV lifted his hand and traced the Sign of the Cross over a glistening block of ice, the cameras flashed, the crowd cheered softly, and the world took note.

It was supposed to be a simple gesture — an act of solidarity with the planet during the Vatican-backed session of the World Climate Summit for Climate Justice in Rome.

But what began as a visual symbol for environmental harmony quickly spiraled into a global debate about faith, optics, and the uneasy marriage between theology and ideology.

The moment was brief — thirty seconds of papal solemnity surrounded by blue banners meant to resemble a flowing river.

Yet, in those thirty seconds, an avalanche of reactions began. Within hours, images of the Pope blessing the ice block went viral.

On Catholic social media, the clip was reposted tens of thousands of times, often with sarcastic captions: “Next: Blessing a snowflake for inclusion.”

Others, more reverent, defended it as a creative reminder of the fragility of God’s creation.

But beneath the memes, a deeper tension was exposed — one that cuts to the core of what the modern papacy has become: a balancing act between spiritual tradition and political messaging.

A Blessing or a Performance?

In Catholic theology, the act of blessing is profound. Priests bless people, homes, crops, even tools — anything that contributes to human flourishing under God’s providence.

But blessing a melting block of ice in front of world leaders? That’s not in any catechism.

To the faithful, it was the optics — not the theology — that stung. “We bless all kinds of things in the Catholic Church,” noted Catholic radio host Joe McClane on his program A Catholic Take.

“But it’s the image — the meme of it — that’s the problem. While the Church bleeds members and the world mocks the faith, this is what we show: the Pope blessing an ice cube.”

It wasn’t just conservative Catholics who cringed. Even moderate observers within the Vatican privately admitted the photo-op was a miscalculation.

“It played too easily into the narrative that the Church has become a stage for global politics rather than a voice for divine truth,” one Vatican insider told La Verità on background.

The papal gesture, they explained, had been planned by the event’s climate committee to “represent the cry of the earth.” The melting ice was supposed to symbolize both ecological suffering and the passage of time — humanity’s fleeting window to act.

But for many believers, the image raised another, far more uncomfortable question: If the Pope can bless the climate, why can’t he heal the confusion within his own Church?

A Church Divided — Again

That question struck a chord because it came on the heels of another storm — Pope Leo’s controversial remarks comparing the death penalty to abortion.

The statement, made only days before the climate summit, shocked many traditional Catholics.

“If you support the death penalty, you are not truly pro-life,” the Pope had declared.

For theologians like Nicholas Kavasos, a young traditionalist commentator, the statement was nothing short of revolutionary — and not in a good way.

“You’re talking about overturning two millennia of moral teaching in a single sound bite,” Kavasos said on McClane’s broadcast.

“When you say the death penalty is contrary to the Gospel, you’re not just critiquing governments — you’re contradicting Scripture, Church Fathers, and saints. That’s not development of doctrine. That’s doctrinal chaos.”

To him, the ice block wasn’t just a gimmick. It was a metaphor for the papacy itself: melting under the heat of modern ideology.

Optics and Outrage

The timing couldn’t have been worse. As social media flooded with clips of the Pope’s blessing, critics juxtaposed it against footage from Nigeria and the Congo, where Christians are routinely slaughtered by Islamist extremists.

“Where is the same level of concern for them?” asked Catholic author Michael Knowles.

“If we can bless an ice block, can we not bless the persecuted Church?”

That sentiment echoed widely. In the eyes of many Catholics, the papal focus on climate symbolism and interfaith messaging — seen again in a video released the same week, showing Pope Leo praying alongside leaders of other religions for “universal peace” — seemed to confirm their fears that the Church’s moral compass had drifted toward a kind of eco-humanism.

And yet, from the Vatican’s perspective, this was precisely the point. “The Pope’s gesture was a call for unity — not only among Catholics but among all humanity,” a Vatican spokesperson told reporters afterward.

“The melting ice symbolizes not destruction, but conversion. Just as water flows and gives life, the Church calls all people to renew their relationship with creation.”

It was a poetic defense. But in the court of public opinion, poetry often loses to memes.

A Meme for the Ages

Within hours, the internet did what it does best: recontextualize. The image of Pope Leo blessing the ice began to circulate with captions like “When your soul is lukewarm” or “The new holy water starter pack.”

Even secular outlets picked up on the frenzy, with Politico calling it “one of the strangest PR moments of the modern papacy.”

“It’s not that Catholics object to environmental concern,” one communications analyst observed.

“It’s that they resent feeling preached to about climate change while moral clarity on core issues like life, marriage, and sin seems to evaporate.”

In other words, the ice wasn’t just melting — trust was too.

The “Francis Effect,” Reloaded

Observers of Vatican politics have seen this before. Pope Francis’ papacy was marked by similar flashpoints — washing the feet of Muslim refugees, appearing in eco-documentaries, and hosting interreligious “prayer for peace” events in Assisi.

To admirers, those were moments of courage and inclusion. To critics, they were dangerous flirtations with relativism.

Now, with Pope Leo XIV, an American-born pontiff fluent in modern media strategy, those tensions have only deepened.

His supporters hail him as a bridge-builder — a man of dialogue and compassion. His detractors call him “Francis with better English.”

And unlike his predecessors, Leo’s controversies have an immediacy that comes from speaking directly, without translators, to an English-speaking world hungry for sound bites.

“There’s no buffer,” explains Dr. Maria Del Vecchio, a church historian at Sapienza University in Rome.

“When Pope Francis made ambiguous statements, defenders could say it was lost in translation.

Pope Leo has no such luxury. When he speaks, every word counts — and every word is weaponized.”

Theology vs. Optics

The deeper issue here isn’t the ice block or even climate policy. It’s the growing dissonance between the Church’s spiritual mission and its public persona.

“The Church was founded to save souls,” said Kavasos. “Now it seems more interested in saving ecosystems.”

That accusation might sound harsh, but it resonates with a segment of Catholics who feel alienated by what they see as the Church’s capitulation to secular agendas.

For them, the image of the Pope surrounded by blue banners and secular slogans was the ultimate symbol of misplaced priorities.

And yet, others defend the gesture as profoundly consistent with Catholic teaching on stewardship.

“Creation is a gift,” argues Sister Caterina Rossi, a theologian specializing in Catholic environmental ethics.

“To bless the earth, even in symbolic form, is to remind humanity of our sacred duty to protect it.

The Holy Father’s action was not a political stunt — it was a prayer made visible.”

Still, even Sister Rossi admits the Vatican could have managed the “optics” better.

“The Church must communicate eternal truths in modern ways,” she says, “but without appearing trivial.”

The Politics Beneath the Piety

There’s another layer to all this — the geopolitics of global religion.

Every pope since Paul VI has sought to engage the world stage, but Pope Leo has taken it further, partnering with international institutions that many Catholics view with suspicion.

His visit to the World Climate Summit placed him alongside figures who advocate population control, gender ideology, and technocratic governance — all antithetical to Catholic teaching.

To some, that’s not outreach; it’s compromise. “You don’t evangelize by baptizing the language of globalism,” said theologian Christopher Ferrara. “You end up sanctifying it.”

Indeed, the papal blessing of the ice block wasn’t just a religious moment — it was a photo op in a secular narrative, one where the Church risks being recast not as guardian of divine law but as chaplain to the global order.

Faith in the Age of Performance

Perhaps that’s why this single act — a blessing most would have forgotten in a day — has lingered in the public consciousness.

It felt staged, performative, curated for the cameras rather than for the faithful. And yet, paradoxically, it may have revealed more truth than intended.

Like the ice melting slowly before him, the Pope’s gesture symbolized something fragile and fleeting: the Church’s credibility in an age of spectacle.

The faithful are asking for clarity. They are asking for courage. And they are asking for a shepherd who blesses not the symbols of the age, but the souls trapped within it.

Until then, the image will remain — a Pontiff, framed by artificial light, his hand hovering over a melting block of ice.

A gesture meant to cool the planet but which instead ignited a firestorm.

Because everyone saw the water melt that day.

But only a few understood what it really meant.